We are nerds and we know it. We eat, sleep, joke about and critique barcode labels all the time, here at EIM. One of us even owns a pair of barcode label cufflinks. He was busted wearing them at one of our holiday parties. We know, we know. Pathetic.

What’s good about our nerdiness, however, is the fact that—since we know our business so well—you really don’t need to sweat it. We’ve got you covered. Sure, we can do the usual stuff like Code 39 and Code 128. Yet there are a lot of specialized and even downright peculiar barcodes out there in barcode-land. Codes like Interleaved 2 of 5, CPC Binary, EAN, ISBN, Aztec, Datamatrix, Chromocode (which gives you those nice, bright colors and greens of summers—OK, that’s a song by Paul Simon), and QR Code. Some of these are 1-Dimensional (strictly linear) and some of them are 2-Dimensional (non-linear). Dimensions in a barcode? What is a barcode neophyte to do?

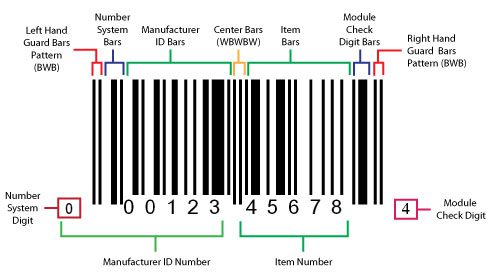

The mapping between messages and barcodes is called a symbology. The specification of a symbology includes the encoding of the single digits or characters of the message, as well as the start and stop characters into bars and space, the size of the quiet zone required before and after the barcode, and for certain types of barcodes, the computation of a checksum.

Just What is a Checksum, Anyway?

A checksum is a computed value from a block of data and which—in the case of barcodes—is stored along with the data in order to detect corruption of the data. Checksums are required elements of barcodes such as Code 128 or UPC. A check digit is an extra character added to a barcode as a redundancy check for error detection—a “digital fingerprint”—used in barcode land. It consists of a single digit computed from the other digits in the message. With a check digit, one can detect simple errors in the input of a series of digits, such as a single mistyped digit or the permutation of two successive digits.

For example, the final digit of a UPC barcode (used on retail products) is the check digit. Let’s say that our check digit is 4 and this is checked as follows:

1. Add the digits (up to but not including the check digit) in the odd-numbered positions (first, third, fifth, etc.) together (0+2+0+0+2+0=4) and multiply by three (4 x 3 = 12)

2. Add the digits (up to but not including the check digit) in the even-numbered positions (second, fourth, sixth, etc.) (1+0+0+0+3=4)

3. Add the two results together to find the sum. (12 + 4 = 16)

4. The check digit will be the smallest number required to round the sum to the nearest multiple of 10. (16 rounds up to 20; 20 – 16 = 4 = the check digit)

You had to ask, didn’t you? If you do all those calculations and the result does not match the check digit, then chances are that a keyboard operator keyed in the wrong number for the barcode somewhere along the line.